High-Tech “Glass-Bottom” Fishing

Benefits of integrating today’s underwater cameras with chartplotter/sonar combos in open water

Benefits of integrating today’s underwater cameras with chartplotter/sonar combos in open water

By Steve Pennaz

I was about 10 years old when I saw a TV program about a Florida tourist operation with glass-bottom boats. I can remember thinking: Wouldn’t that be cool? Even then, my goal was to catch more and bigger fish, and a transparent-floored boat seemed like a good way to learn more about fish location and behavior.

Now, decades later, my dream has come true. I’m fishing out of a glass-bottom boat… Okay, not literally, but outfitted with a unique combination of compatible electronics, my Ranger 620 allows me to see what’s going on below. What’s even better, the system is simple to use, but profound in what it reveals.

My system starts with a

Garmin 7612xsv chartplotter/sonar combo. This unit, like many offered by Garmin, features a video input option that allows me to plug in and view

Aqua-Vu Multi-Vu camera.

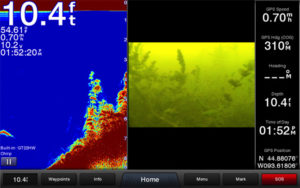

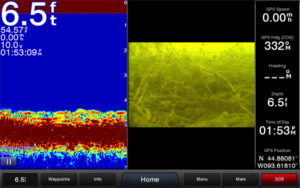

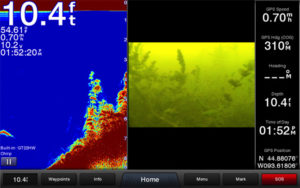

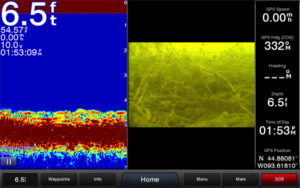

The pair works extremely well together. The 12-inch 1280 x 800 WXGA Garmin display shows what the camera captures in ultra-bright detail, even in full sunlight. It offers the option of full-screen video viewing, or I can split the screen to have video and sonar, video and mapping, etc., all with a push or two on the unit’s touch screen.

Historically, the weak links with underwater cameras has been the monitor quality, a necessity to keep overall cost down, and ease of use.

Although companies like Aqua-Vu are making better and brighter monitors, there are also options like the camera-only Aqua-Vu Multi-Vu that plugs directly into my 10-and 12-inch Garmin units and provides a stunningly clear, large viewing space.

With the press of a couple buttons on the touch screen Garmin menu, I can go from mapping to sonar (traditional sonar, ClearVü or SideVü) or any combination of the two. I also have the option of adding underwater video to the mix.

The ease of incorporating underwater viewing allows me to use the camera far more frequently. I now drop it overboard any time I’m curious, and within seconds get a look at what’s going on below the boat.

I use it often for fish species verification, a huge time saver, especially when filming TV shows, pre-fishing for tournaments, or when trying to put family and friends on fish. It also helped me become a much better interpreter of the highly-detailed CHIRP sonar readings I only dreamed about a few years ago.

It’s also incredibly fun.

Case Study #1: Smallies or Suckers?

I was on the Great Lakes chasing giant smallmouth when I pulled up on a big reef and scanned it my SideVü. It was loaded with fish! Knowing that smallmouths will move onto reefs in late fall, I was pumped especially after catching a four-pounder on my second cast.

I hooked another fish

15 minutes later and had the surprise of the trip. It was a big sucker and it had inhaled my jigging spoon! The next fish was also a sucker, as was the third, and yes, I was baffled! I had no idea that suckers will feed like aggressive predators.

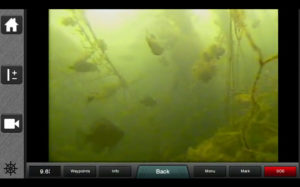

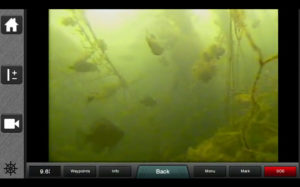

Looking for answers, I finally lowered the Aqua-Vu down and quickly understood what was going on. The marks I was seeing on SideVü were not smallmouth, but suckers, and the reef was crawling with them. We left.

Case Study #2: Walleye and Bass

Earlier this summer, I found a rock pile in 19 feet of water that was loaded with fish. I expected walleyes; but when I dropped the camera I discovered they were all deep-water largemouths. Later that same day, I found additional schools of fish I was convinced were crappies. Again, I dropped the camera and was proved wrong; they were big bluegills.

Another trip sticks out.

I was taping an episode of “Lake Commandos” on a lake that DNR survey data indicated had lots of largemouth, but very few smallmouth. So I was surprised when we landed several smallmouth along a weedline that should have held largies.

So I dropped the camera to the bottom and discovered a huge pile of boulders in the middle of the grass and it was filthy with smallmouth! This was information I couldn’t get from my sonar because thick weeds had overgrown the entire spot.

Vegetation Identification

Many natural lakes have progressively become more diverse in terms of vegetation types. Thousands across the country are now weed-choked with indigenous and invasive vegetation.

On many lakes, weedlines extend for hundreds or even thousands of yards. This makes breaking down the lake difficult and time-consuming, particularly when fish are relating to specific weed types.

On a recent “Lake Commandos” shoot with BASS touring pro Adrian Avena, the key to the entire big bass bite came down to finding cabbage, which was difficult as it was available only in small, random, isolated patches. As soon as we found a patch, however, we’d land two or three 4- to 6- pound bass on jigs tipped with

Berkley Chigger Craws. But you could work 400-600 yards of a weedline between cabbage patches.

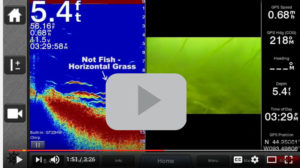

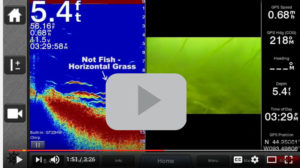

Sonar definition has really improved over the years, to the point that it is making it possible to breakdown some weed types with sonar. Milfoil, for example, looks different on screen than cabbage… if you know what to look for.

By running sonar side-by-side with video, I’ve learned to recognize how various weed types appear on sonar. The lessons continue, and it’s not full-proof, but I find myself able to find grass like coontail and cabbage that usually holds fish and avoid those that typically don’t.

This information is so valuable that I am now investing time simply to compare what I am seeing on sonar with the camera. In the process, I am becoming more efficient at finding fish.

One other thing about grass, and I am embarrassed to admit this: in some cases, particularly in areas with current, isolated patches of soft-stalked grass like milfoil, will lay horizontal to the bottom. On sonar, these areas can look like a school of four to five fish (and I thought they were). Another lesson learned.

Bottom Hardness Identification

Bottom Hardness Identification

My sonar/camera system is also invaluable for confirming bottom composition and clarifying what my sonar is telling me. In many situations, with sonar alone, I was left wondering: Is that rock or thick coontail clumps on bottom. Hard bottom or soft? A bottom transition from one to the other? Now I understand what that looks like on sonar and can validate it 100% of the time with camera, which is critical. Bottom hardness transition areas are underwater super-highways for countless fish species.

Studying bottom composition has led to some interesting discoveries, too. I’ve spotted lost anchors, sunglasses, lures and rods on the bottom of lakes, as well a surprising number of golf balls.

Parting Thoughts

Parting Thoughts

These days, I am dedicating more time to viewing because its making me a more productive fisherman. Oh, it’s fun to drop a camera and drift over cover and get a peak into the underwater world below. “Look, there’s a big smallmouth!”

But what the sonar/underwater combination reveals is much more than just fun… it’s also incredibly educational. I find myself dedicating days to leaving the rods in the locker and studying specific structure. Why is this specific spot holding fish? I’ll study spots for awhile, make mental notes, and drop waypoints, and this is putting more fish in the boat.

Benefits of integrating today’s underwater cameras with chartplotter/sonar combos in open water

By Steve Pennaz

I was about 10 years old when I saw a TV program about a Florida tourist operation with glass-bottom boats. I can remember thinking: Wouldn’t that be cool? Even then, my goal was to catch more and bigger fish, and a transparent-floored boat seemed like a good way to learn more about fish location and behavior.

Now, decades later, my dream has come true. I’m fishing out of a glass-bottom boat… Okay, not literally, but outfitted with a unique combination of compatible electronics, my Ranger 620 allows me to see what’s going on below. What’s even better, the system is simple to use, but profound in what it reveals.

My system starts with a Garmin 7612xsv chartplotter/sonar combo. This unit, like many offered by Garmin, features a video input option that allows me to plug in and view Aqua-Vu Multi-Vu camera.

The pair works extremely well together. The 12-inch 1280 x 800 WXGA Garmin display shows what the camera captures in ultra-bright detail, even in full sunlight. It offers the option of full-screen video viewing, or I can split the screen to have video and sonar, video and mapping, etc., all with a push or two on the unit’s touch screen.

Benefits of integrating today’s underwater cameras with chartplotter/sonar combos in open water

By Steve Pennaz

I was about 10 years old when I saw a TV program about a Florida tourist operation with glass-bottom boats. I can remember thinking: Wouldn’t that be cool? Even then, my goal was to catch more and bigger fish, and a transparent-floored boat seemed like a good way to learn more about fish location and behavior.

Now, decades later, my dream has come true. I’m fishing out of a glass-bottom boat… Okay, not literally, but outfitted with a unique combination of compatible electronics, my Ranger 620 allows me to see what’s going on below. What’s even better, the system is simple to use, but profound in what it reveals.

My system starts with a Garmin 7612xsv chartplotter/sonar combo. This unit, like many offered by Garmin, features a video input option that allows me to plug in and view Aqua-Vu Multi-Vu camera.

The pair works extremely well together. The 12-inch 1280 x 800 WXGA Garmin display shows what the camera captures in ultra-bright detail, even in full sunlight. It offers the option of full-screen video viewing, or I can split the screen to have video and sonar, video and mapping, etc., all with a push or two on the unit’s touch screen. Historically, the weak links with underwater cameras has been the monitor quality, a necessity to keep overall cost down, and ease of use.

Although companies like Aqua-Vu are making better and brighter monitors, there are also options like the camera-only Aqua-Vu Multi-Vu that plugs directly into my 10-and 12-inch Garmin units and provides a stunningly clear, large viewing space.

With the press of a couple buttons on the touch screen Garmin menu, I can go from mapping to sonar (traditional sonar, ClearVü or SideVü) or any combination of the two. I also have the option of adding underwater video to the mix.

The ease of incorporating underwater viewing allows me to use the camera far more frequently. I now drop it overboard any time I’m curious, and within seconds get a look at what’s going on below the boat.

I use it often for fish species verification, a huge time saver, especially when filming TV shows, pre-fishing for tournaments, or when trying to put family and friends on fish. It also helped me become a much better interpreter of the highly-detailed CHIRP sonar readings I only dreamed about a few years ago. It’s also incredibly fun.

Case Study #1: Smallies or Suckers?

I was on the Great Lakes chasing giant smallmouth when I pulled up on a big reef and scanned it my SideVü. It was loaded with fish! Knowing that smallmouths will move onto reefs in late fall, I was pumped especially after catching a four-pounder on my second cast.

I hooked another fish 15 minutes later and had the surprise of the trip. It was a big sucker and it had inhaled my jigging spoon! The next fish was also a sucker, as was the third, and yes, I was baffled! I had no idea that suckers will feed like aggressive predators.

Looking for answers, I finally lowered the Aqua-Vu down and quickly understood what was going on. The marks I was seeing on SideVü were not smallmouth, but suckers, and the reef was crawling with them. We left.

Case Study #2: Walleye and Bass

Earlier this summer, I found a rock pile in 19 feet of water that was loaded with fish. I expected walleyes; but when I dropped the camera I discovered they were all deep-water largemouths. Later that same day, I found additional schools of fish I was convinced were crappies. Again, I dropped the camera and was proved wrong; they were big bluegills.

Another trip sticks out.

I was taping an episode of “Lake Commandos” on a lake that DNR survey data indicated had lots of largemouth, but very few smallmouth. So I was surprised when we landed several smallmouth along a weedline that should have held largies.

So I dropped the camera to the bottom and discovered a huge pile of boulders in the middle of the grass and it was filthy with smallmouth! This was information I couldn’t get from my sonar because thick weeds had overgrown the entire spot.

Vegetation Identification

Historically, the weak links with underwater cameras has been the monitor quality, a necessity to keep overall cost down, and ease of use.

Although companies like Aqua-Vu are making better and brighter monitors, there are also options like the camera-only Aqua-Vu Multi-Vu that plugs directly into my 10-and 12-inch Garmin units and provides a stunningly clear, large viewing space.

With the press of a couple buttons on the touch screen Garmin menu, I can go from mapping to sonar (traditional sonar, ClearVü or SideVü) or any combination of the two. I also have the option of adding underwater video to the mix.

The ease of incorporating underwater viewing allows me to use the camera far more frequently. I now drop it overboard any time I’m curious, and within seconds get a look at what’s going on below the boat.

I use it often for fish species verification, a huge time saver, especially when filming TV shows, pre-fishing for tournaments, or when trying to put family and friends on fish. It also helped me become a much better interpreter of the highly-detailed CHIRP sonar readings I only dreamed about a few years ago. It’s also incredibly fun.

Case Study #1: Smallies or Suckers?

I was on the Great Lakes chasing giant smallmouth when I pulled up on a big reef and scanned it my SideVü. It was loaded with fish! Knowing that smallmouths will move onto reefs in late fall, I was pumped especially after catching a four-pounder on my second cast.

I hooked another fish 15 minutes later and had the surprise of the trip. It was a big sucker and it had inhaled my jigging spoon! The next fish was also a sucker, as was the third, and yes, I was baffled! I had no idea that suckers will feed like aggressive predators.

Looking for answers, I finally lowered the Aqua-Vu down and quickly understood what was going on. The marks I was seeing on SideVü were not smallmouth, but suckers, and the reef was crawling with them. We left.

Case Study #2: Walleye and Bass

Earlier this summer, I found a rock pile in 19 feet of water that was loaded with fish. I expected walleyes; but when I dropped the camera I discovered they were all deep-water largemouths. Later that same day, I found additional schools of fish I was convinced were crappies. Again, I dropped the camera and was proved wrong; they were big bluegills.

Another trip sticks out.

I was taping an episode of “Lake Commandos” on a lake that DNR survey data indicated had lots of largemouth, but very few smallmouth. So I was surprised when we landed several smallmouth along a weedline that should have held largies.

So I dropped the camera to the bottom and discovered a huge pile of boulders in the middle of the grass and it was filthy with smallmouth! This was information I couldn’t get from my sonar because thick weeds had overgrown the entire spot.

Vegetation Identification

Many natural lakes have progressively become more diverse in terms of vegetation types. Thousands across the country are now weed-choked with indigenous and invasive vegetation.

On many lakes, weedlines extend for hundreds or even thousands of yards. This makes breaking down the lake difficult and time-consuming, particularly when fish are relating to specific weed types.

On a recent “Lake Commandos” shoot with BASS touring pro Adrian Avena, the key to the entire big bass bite came down to finding cabbage, which was difficult as it was available only in small, random, isolated patches. As soon as we found a patch, however, we’d land two or three 4- to 6- pound bass on jigs tipped with Berkley Chigger Craws. But you could work 400-600 yards of a weedline between cabbage patches.

Sonar definition has really improved over the years, to the point that it is making it possible to breakdown some weed types with sonar. Milfoil, for example, looks different on screen than cabbage… if you know what to look for.

By running sonar side-by-side with video, I’ve learned to recognize how various weed types appear on sonar. The lessons continue, and it’s not full-proof, but I find myself able to find grass like coontail and cabbage that usually holds fish and avoid those that typically don’t.

This information is so valuable that I am now investing time simply to compare what I am seeing on sonar with the camera. In the process, I am becoming more efficient at finding fish.

One other thing about grass, and I am embarrassed to admit this: in some cases, particularly in areas with current, isolated patches of soft-stalked grass like milfoil, will lay horizontal to the bottom. On sonar, these areas can look like a school of four to five fish (and I thought they were). Another lesson learned.

Many natural lakes have progressively become more diverse in terms of vegetation types. Thousands across the country are now weed-choked with indigenous and invasive vegetation.

On many lakes, weedlines extend for hundreds or even thousands of yards. This makes breaking down the lake difficult and time-consuming, particularly when fish are relating to specific weed types.

On a recent “Lake Commandos” shoot with BASS touring pro Adrian Avena, the key to the entire big bass bite came down to finding cabbage, which was difficult as it was available only in small, random, isolated patches. As soon as we found a patch, however, we’d land two or three 4- to 6- pound bass on jigs tipped with Berkley Chigger Craws. But you could work 400-600 yards of a weedline between cabbage patches.

Sonar definition has really improved over the years, to the point that it is making it possible to breakdown some weed types with sonar. Milfoil, for example, looks different on screen than cabbage… if you know what to look for.

By running sonar side-by-side with video, I’ve learned to recognize how various weed types appear on sonar. The lessons continue, and it’s not full-proof, but I find myself able to find grass like coontail and cabbage that usually holds fish and avoid those that typically don’t.

This information is so valuable that I am now investing time simply to compare what I am seeing on sonar with the camera. In the process, I am becoming more efficient at finding fish.

One other thing about grass, and I am embarrassed to admit this: in some cases, particularly in areas with current, isolated patches of soft-stalked grass like milfoil, will lay horizontal to the bottom. On sonar, these areas can look like a school of four to five fish (and I thought they were). Another lesson learned.

Bottom Hardness Identification

My sonar/camera system is also invaluable for confirming bottom composition and clarifying what my sonar is telling me. In many situations, with sonar alone, I was left wondering: Is that rock or thick coontail clumps on bottom. Hard bottom or soft? A bottom transition from one to the other? Now I understand what that looks like on sonar and can validate it 100% of the time with camera, which is critical. Bottom hardness transition areas are underwater super-highways for countless fish species.

Studying bottom composition has led to some interesting discoveries, too. I’ve spotted lost anchors, sunglasses, lures and rods on the bottom of lakes, as well a surprising number of golf balls.

Bottom Hardness Identification

My sonar/camera system is also invaluable for confirming bottom composition and clarifying what my sonar is telling me. In many situations, with sonar alone, I was left wondering: Is that rock or thick coontail clumps on bottom. Hard bottom or soft? A bottom transition from one to the other? Now I understand what that looks like on sonar and can validate it 100% of the time with camera, which is critical. Bottom hardness transition areas are underwater super-highways for countless fish species.

Studying bottom composition has led to some interesting discoveries, too. I’ve spotted lost anchors, sunglasses, lures and rods on the bottom of lakes, as well a surprising number of golf balls.

Parting Thoughts

These days, I am dedicating more time to viewing because its making me a more productive fisherman. Oh, it’s fun to drop a camera and drift over cover and get a peak into the underwater world below. “Look, there’s a big smallmouth!”

But what the sonar/underwater combination reveals is much more than just fun… it’s also incredibly educational. I find myself dedicating days to leaving the rods in the locker and studying specific structure. Why is this specific spot holding fish? I’ll study spots for awhile, make mental notes, and drop waypoints, and this is putting more fish in the boat.

Parting Thoughts

These days, I am dedicating more time to viewing because its making me a more productive fisherman. Oh, it’s fun to drop a camera and drift over cover and get a peak into the underwater world below. “Look, there’s a big smallmouth!”

But what the sonar/underwater combination reveals is much more than just fun… it’s also incredibly educational. I find myself dedicating days to leaving the rods in the locker and studying specific structure. Why is this specific spot holding fish? I’ll study spots for awhile, make mental notes, and drop waypoints, and this is putting more fish in the boat.